Searching for Franklin

Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site

After 2 years with no news of the Franklin expedition, the British government sent out the first search parties. Decades of expeditions followed and searchers scoured the Arctic, at first hoping to find the men and ships, and later simply trying to find surviving documents and piece together what had happened. Tantalizing clues kept the mystery alive throughout the decades. Parks Canada and its partners led 21st century searches.

In the aftermath of Franklin’s disappearance

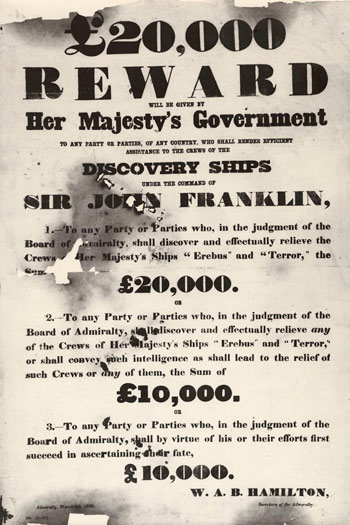

Since the 16th century, many Europeans had been obsessed with finding a northern route to Asia from the Atlantic to the Pacific. In Great Britain, this interest had been revitalised in 1818. The Franklin Expedition set out in 1845 with the same hope as all the other past expeditions: to successfully chart the elusive Northwest Passage. Two years passed with no news, and people back home became concerned. A substantial reward, a distraught wife, and eventual evidence of cannibalism all heightened the drama. Decades of search followed.

Early searches

John Rae’s overland expedition

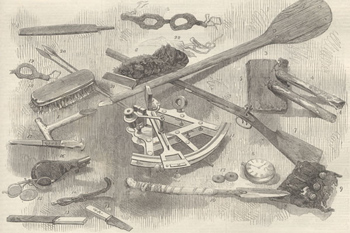

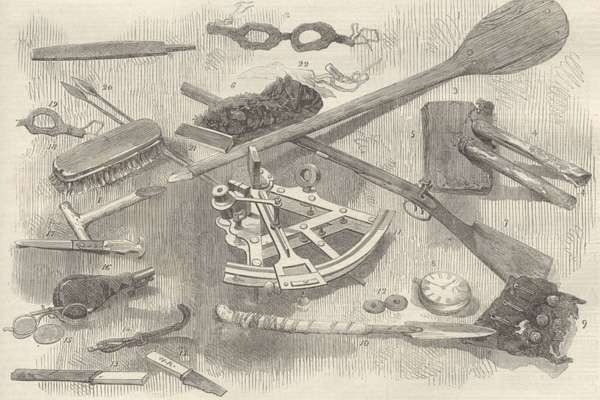

During a search expedition in 1854, Arctic explorer John Rae heard Inuit accounts of lost and starving Qallunaat (white men) being spotted 4 years earlier – accounts that included reports of cannibalism. Rae acquired undeniable evidence from Inuit: a silver plate, pieces of cutlery (some with initials identifying as belonging to officers), and Franklin’s medal of the Royal Hanoverian Order presented to him at his knighting. Rae returned to England with his information before another winter closed in.

Rae’s report drew strong criticism. Lady Franklin condemned Rae for failing to confirm the Inuit reports with further searching. She accused him of rushing home to collect the Admiralty’s reward money. Lady Franklin pressed famed writer Charles Dickens to publicly discredit Rae’s information. Dickens wrote a two-part article in his journal Household Words, stating that “civilized” British naval officers would never resort to cannibalism and accused the “treacherous” Inuit of murdering Franklin’s men. Rae’s response to Dickens, defending his Inuit informants, was also published in two later editions.

Francis McClintock’s 1859 finds

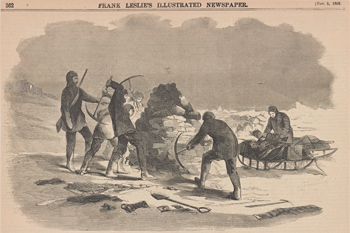

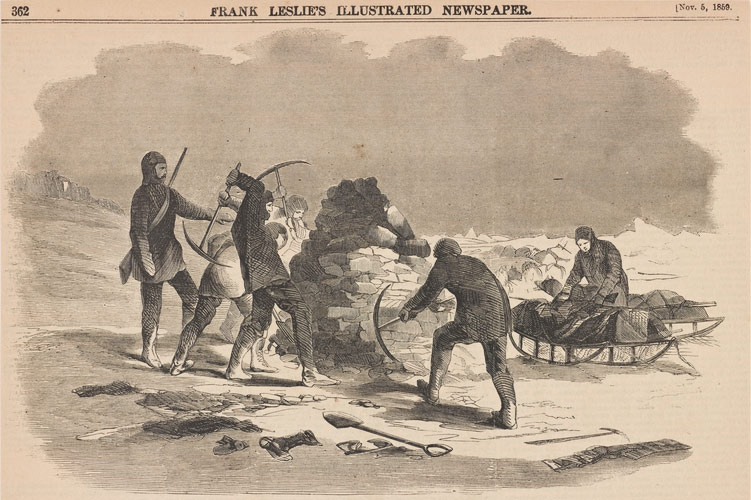

Following Rae’s report, Lady Franklin engaged Francis McClintock to continue the search. He travelled to King William Island, where he and his second in command, Lieutenant William Hobson, searched for survivors. Hobson’s party explored the west coast, and McClintock’s party travelled east. At two Inuit camps, McClintock recovered additional silverware and wooden items from HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. As he travelled farther, he examined more evidence of the fate of the Franklin crew, including a heavy sledge carrying a ship’s boat. Most tellingly, McClintock’s expedition discovered skeletons, graves, and abandoned articles such as books and clothing.

Meanwhile, Hobson had found a stone cairn on Victory Point. Inside was a metal tube containing a single sheet of paper, on which were written two messages. The first, written in May 1847, confirmed that the expedition had spent their winter at Beechey Island and had been trapped by ice since September 1846. The message concluded with a cheery “all well”.

The second message, added to the same paper in April 1848, had a different tone. Signed by captains Francis Crozier and James Fitzjames, the message reported that a total of nine officers and 15 men had died to date, including Sir John Franklin (on June 11, 1847). They wrote that the 105 survivors had abandoned ships and were heading south to the Great Fish (Back) River.

Franklin’s legacy

The search for the Franklin Expedition helped map the Canadian Arctic. Eventually, the Northwest Passage was found and charted. With the discovery of the note at the Victory Point cairn, a chapter of the Franklin Expedition closed. But more questions remained.

Were members of the Franklin crew aware they had found the Northwest Passage? Lady Franklin believed this to be true. She spent many of her last years of life trying to establish the discovery as part of Franklin’s legacy.

As time passed, the question changed to: What happened to the ships and its crews? Search expeditions and interest continued for the rest of the 19th century and throughout the decades that follow.

Charles Francis Hall discovers valuable info

The search for Franklin inspired many people outside of Britain and Canada. Charles Francis Hall was an American journalist who was fascinated with the Franklin story. He believed that survivors from the expedition would be found living among the Inuit.

From 1860-1871 Hall traveled throughout the region, interviewed Inuit and collected testimony about European visitors. These accounts were collected with the help of two Inuit translators and guides who became Hall’s friends; Taqulittuq and Ipiivik. The two were also known as Hannah and Joseph.

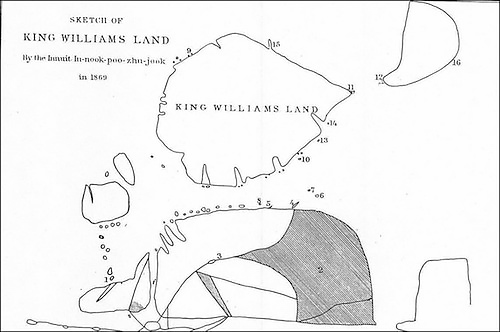

Inukpujijuq, an Inuk from the region provided a significant piece of information. He talked about visiting the ship as a child and identified its location south of King William Island. Hall’s reports and interviews served as valuable documents throughout the years. They were used to help other searches including Parks Canada’s. In 2014, the wreck of HMS Erebus was found in the region previously identified by Inukpujijuq.

Frederick Schwatka’s extensive journey

Frederick Schwatka was another American explorer committed to finding answers about the fate of Franklin’s men. Between 1879 and 1880, Schwatka and a small group of companions, including Inuit, journeyed 5,232 kilometres by sled, the longest on record at the time.

Like Rae and Hall, Schwatka travelled and lived using Inuit techniques. He collected many relics from the Franklin expedition. Schwatka located the King William Island area and also recorded additional Inuit accounts. The only document he located was a copy of the record found by Hobson in 1859 during McClintock’s expedition. Ipiivik, who had travelled with Hall, also served as Schwatka’s guide and translator.

Twenty-first century searches

The disappearance of the two ships with its 129 officers and men captured public attention and interest for more than 160 years. Over the years, various individuals and groups studied the evidence, developed their own theories and undertook searches. In 1992, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada designated the wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror as a national historic site in order to protect them if they were ever found. This designation along with a 1997 agreement with the British government gave Parks Canada a role in finding and protecting the ships.

In 2008, Parks Canada’s Underwater Archaeology Team, supported by a variety of collaborators, began a new multi-year series of modern searches. Perseverance, technology and Inuit knowledge lead to the discovery of HMS Erebus in 2014 and HMS Terror in 2016.

- Date modified :